Vitamin K and Warfarin – A Combo You Don’t Want

If you have been prescribed the anti-coagulant (blood thinning) drug, warfarin — which is sold under a number of brand names, including Jantoven, Marevan, Uniwarfin, Lawarin and Waran — you must carefully avoid all supplements containing vitamin K, particularly in the form of vitamin K2. If you are looking for a supplement without vitamin K for bone health, try AlgaeCal Basic.

Even your consumption of foods rich in vitamin K1, such as leafy green vegetables, must be carefully monitored and restricted when taking warfarin. Here’s why.

Warfarin Prevents Blood Clot Formation by Blocking Vitamin K Activity

Warfarin works by blocking the activity of an enzyme called vitamin K epoxide reductase (VKOR). This is the enzyme that recycles vitamin K after it has been used to activate the vitamin K-dependent proteins (both the blood clotting proteins our bodies prefer to activate using vitamin K1, and the proteins that regulate where calcium is deposited in the body, which are activated by K2).

The VKOR enzyme adds electrons back to the used (oxidized) forms of vitamin K1 or K2, so they are able to go to work again. Warfarin blocks the VKOR enzyme, preventing vitamin K, once used, from being recycled, which greatly reduces the amount of available vitamin K. Plus, to lessen their risk of excessive blood clot formation, people on warfarin are told to not introduce much vitamin K into their bodies, even by eating foods rich in vitamin K, so their vitamin K supplies are already low. Warfarin then eliminates the body’s ability to recycle the tiny amount of vitamin K that is present.

Not Getting Enough Vitamin K Causes Serious Harm to Your Blood Vessels, Kidneys and Bones

The problem with this is that while the warfarin drugs lower risk of excessive blood clot formation by preventing vitamin K’s activation of certain blood clotting proteins, these drugs also prevent vitamin K (in both its forms as vitamin K1 and vitamin K2), from doing its other jobs. Not getting these vitamin K-dependent jobs done causes serious harm to your blood vessels, kidneys and bones.

Vitamin K1 is highly anti-inflammatory, which is one reason eating lots of leafy greens helps protect our cardiovascular system and kidneys from damage caused by oxidative stress (out of control free radicals), and our bones from osteopenia/osteoporosis due to excessive osteoclast activity (anything that causes chronic inflammation results in over-activation of osteoclasts and promotes bone loss).

Vitamin K2 activates the two proteins that regulate where calcium goes in your body: osteocalcin and matrix Gla protein. Osteocalcin is responsible for pulling calcium into your bones, and matrix Gla protein is responsible for keeping calcium out of your soft tissues, including your heart, blood vessels, kidneys, breasts and brain. Without vitamin K2 to activate them, neither osteocalcin nor matrix Gla protein work. Calcium deposits in your heart, blood vessels, kidneys, breasts and brain instead of in your bones. Your soft tissues stop working properly because they calcify, while your bones become porous and fragile.(1)(2)(3)

In numerous studies, individuals on warfarin have been shown to have high levels of inactive matrix Gla protein (called ucMGP, which stands for uncarboxylated matrix Gla protein). Medical researchers have also looked at patients’ blood levels of inactive matrix Gla protein (unMGP) before and after they were put on warfarin. Their blood levels of unMGP go way up when taking warfarin, but drop after supplementation with vitamin K. When unMGP levels increase, so does your risk for calcifying your heart, arteries, blood vessels in your kidneys, etc.(4)(5)(6)(7)(8)(9)

Similarly, warfarin has been shown, in numerous studies, to increase levels of uncarboxylated osteocalcin (unOC), to be associated with lowered bone mass and to increase risk for fracture.(10)(11)(12)(13)(14)(15)(16)(17)

One of the more recent studies showing warfarin’s unhappy effects on blood vessels compared mammograms between women who were treated with warfarin to those of women matched in age and diabetes status who were not taking warfarin. No difference was found between the two groups before warfarin use, but after treatment with warfarin, the treated group developed calcified vessels at a rate 50% greater than controls. In patients who were treated with warfarin for more than 5 years, the prevalence of vascular calcification increased to nearly 75%.(18)(19)

Another recent study reported that warfarin, when taken with drugs used to manage type 2 diabetes (the commonly used sulfonylurea drugs, glipizide [brand name Glucotrol], and glimpiride [brand name Glimper]) increased risk for emergency department visits for fall related fractures by 47%, and for hospital admission or emergency department visits for hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) by 22% in those 65-74 years old.(20)

Warfarin has also been shown to significantly increase risk for “intracranial hemorrhage” (bleeding inside the brain, which can cause a stroke). Confirming the findings of earlier studies published in 2014 and 2015, a study, published March 9, 2016, of nearly 32,000 U.S. veterans, aged 75 and older, with atrial fibrillation (a common heart rhythm disorder), found that almost one in three suffered an intracranial bleed while taking warfarin.(21)(22)(23)

If you are taking warfarin, minimizing your risk of a brain bleed is one of the reasons it is so important to monitor the rate at which your blood clots (your INR, explained next) to ensure you are not taking too high a dose of these drugs.

Warfarin Dosing Must Be Frequently Monitored By Checking How Quickly Your Blood Clots

Doctors’ check how high a dose of warfarin is needed to prevent the amount of available vitamin K from increasing by looking at the patient’s INR. INR stands for international normalized ratio, which is a measure of how long it takes prothrombin, one of the blood clotting enzymes activated by vitamin K1, to activate and form a clot.

The target INR level varies from individual to individual. It’s 2–3 in most conditions, but may be 2.5-3.5 or even as high as 3.0-4.5, for example, in patients with mechanical heart valves. If upon testing, the INR is higher than the prescribing physician has determined is optimal for the specific patient, this means that it is taking too long for blood to clot and increasing the risk of a bleed, so the dose of warfarin (which prevents clot formation by preventing vitamin K recycling) will be lowered. If the INR is too low, this means the tendency to form a clot is still elevated, so the dose of warfarin will be increased.

An INR that is too high indicates increased risk of excessive bleeding due to impaired (in this case, by warfarin) ability to produce the blood clots needed to prevent you from bleeding to death from even a tiny cut. An INR that is too low indicates the potential for excessive blood clot formation. When a patient’s INR is high, the doctor will lower the dose of warfarin to protect against a bleed. When the patient’s INR is too low, the doctor will increase the dose of warfarin to protect against excessive clot formation. The key factor for those taking warfarin is maintaining a stable intake of vitamin K against which the appropriate dose of warfarin can be determined, and this requires frequent monitoring of the individual’s INR.

If Taking Warfarin, Small Amounts of Dietary Vitamin K1 Are Safe

Research conducted back in 2007 had shown that vitamin K1 only affects the INR at a dose of 315 micrograms per day, and at this dose, vitamin K1 causes only a small decrease in INR — from 2.0 to 1.5. So, even those taking warfarin can eat some leafy green vegetables if their INR is frequently checked by their physician, so their dose can be adjusted accordingly. The f oods rich enough in vitamin K1 to significantly decrease a person’s INR are the leafy greens along with a few unrefined, unhydrogenated oils.

oods rich enough in vitamin K1 to significantly decrease a person’s INR are the leafy greens along with a few unrefined, unhydrogenated oils.

You’d have to eat a fair amount of leafy greens to consume 315 micrograms of vitamin K1. If you eat spinach, you can have 2.5 cups, and if you prefer lettuce, you’d have to eat around 5 cups to get 315 micrograms of K1. You should not have more than a half-cup of kale; one cup will give you 547 micrograms, but kale delivers the most vitamin K1 of all the leafy greens. Oils are not a problem for people on warfarin. Even unrefined oils provide very little K1: a tablespoon of soybean oil will give you just 25 micrograms, canola oil only 17 micrograms and olive oil just 8 micrograms.

Vitamin K2 In Its MK-7 Form, However, Is Off-Limits

When researchers looked at the effect of MK-7 on INR, MK-7 was found to be much more potent than K1 or the MK-4 form of vitamin K2.

In the initial research published in 2007, it only took 130 micrograms per day of MK-7 to cause a drop in INR from 2.0 to 1.5, so a dose of no more than 50 micrograms per day, which only caused a 10% drop in INR, was thought to be safe for patients on warfarin.

MK-7 supplements are sold in a dose as low as 45 micrograms, and in the Netherlands (where the leading vitamin K researchers in the world conducted this research), they eat a lot of cheese, so it’s not unusual to consume this much MK-7 and other longer-chain menaquinones in the diet. A 50 microgram dose is comparable to the long-chain menaquinone content of 75 to 100 grams (about 3 ounces) of the cheeses richest in K2: English blue cheese, Swiss Emmental and Norwegian Jarlsberg.

The researchers also hoped that because MK-7 remains active in the body for 3-4 days (as long as 96 hours), if 50 micrograms of MK-7 were consumed daily along with properly adjusted doses of warfarin, the patient’s INR would remain stable within a range that would prevent too much blood clot formation, and risk for heart and blood vessel calcification and bone loss would be lessened.

The researchers also hoped that because MK-7 remains active in the body for 3-4 days (as long as 96 hours), if 50 micrograms of MK-7 were consumed daily along with properly adjusted doses of warfarin, the patient’s INR would remain stable within a range that would prevent too much blood clot formation, and risk for heart and blood vessel calcification and bone loss would be lessened.

Now for the bad news. They ran a study to check this theory. The results were published in 2013, and their hopes did not pan out.(24)

Even very low doses of vitamin K2 are contraindicated if you are taking warfarin.

The research revealed that MK-7 in doses as low as 10 – 20 micrograms per day decreased both the INR and the amount of inactive prothrombin (the key blood clotting enzyme whose activity is blocked by warfarin) by 40% in the entire group of 18 patients (yes, this was a small study, but still, not looking good for K2 if you’re taking warfarin).

Daily intakes of 10 and 20 micrograms of MK-7 were found to lower the INR in at least 40% and 60% of subjects, respectively, and to significantly increase blood clot formation by 20% and 30%, respectively. And, even worse, these tiny doses of MK-7 had no beneficial effect on increasing activation of matrix Gla protein, which was what they measured because this is the vitamin K-dependent protein that prevents calcium from depositing in blood vessels. Virtually all the MK-7 got side-tracked to activate blood clotting proteins /prothrombin.

This makes sense: your body will first use vitamin K to ensure you don’t bleed out from a paper cut, and only after this need has been met will any form of vitamin K you consume be used to prevent your bones from breaking and your blood vessels from calcifying.(25)

So, what this study showed was increased risk for blood clot formation plus no benefit from MK-7. In the discussion section of the paper, the researchers also noted, “any benefits of MK-7 accumulation in bone would be offset by increased liver concentrations that would necessitate an increased dose of VKA [vitamin K antagonists/coumarins].” The conclusion drawn: “use of MK-7 supplements needs to be avoided in patients on warfarin therapy.”

Now, for the good news.

If Prescribed Warfarin For Heart Failure, You May Be Able To Use Aspirin Instead

Obviously, you must work with your doctor if you decide this is worth investigating. Research presented at the American Stroke Association’s International Stroke Conference in New Orleans, February 5, 2012, showed that aspirin is just as effective as warfarin for heart failure patients.

This study, which involved 2,305 heart failure patients, found no overall difference in risk of death or for either form of stroke (intracranial hemorrhage or ischemic stroke) between those who received aspirin and those who received warfarin. Researchers also noted warfarin had a higher risk of causing major bleeding events. Aspirin similar to warfarin in stroke prevention, article available at http://news.nurse.com/article/20120205/NATIONAL02/102130013, accessed 3-210-16.

New drugs have become available that prevent clot formation in a different way than the warfarin drugs, and vitamin K1 and K2 can be taken when using these drugs.

You won’t need to avoid leafy greens or supplemental vitamin K2 if you can be switched over to either of two new types of anticoagulant drugs: Factor Xa inhibitors (e.g., rivaroxaban, apixaban) or the direct thrombin inhibitor, dabigatran.

The warfarin drugs are also called Vitamin K Antagonists because they prevent clot formation by preventing the recycling of vitamin K and thus causing a severe drop in vitamin K availability. This prevents clot formation because vitamin K is required for the production of prothrombin and several other enzymes involved in the initiation (beginning) phase of the clotting cascade, but it also prevents activation of all the vitamin K-dependent proteins, including osteocalcin and matrix Gla protein.

The Factor Xa inhibitors prevent blood clot formation by blocking the activity of Factor Xa, an enzyme involved in the later stages of blood clot formation, so vitamin K does not lessen their anticlotting effects.

The direct thrombin inhibitors, as their name implies, bind to already formed thrombin, another enzyme even further down the line of actions required for blood clot formation, and directly block its clot-forming actions. So, again, vitamin K has no impact on their anti-clotting effects.

And these new drugs are more convenient to use. The Factor Xa and direct thrombin inhibitors do not require INR monitoring and need only be taken once daily.

Initially, the newer oral anticoagulant drugs had a major drawback: no antidote to use as a rescue therapy in cases of excessive bleeding. (Vitamin K is the antidote used to stop excessive bleeding caused by warfarin.) Now, however, antidote drugs have been developed that effectively reverse the anticoagulant effects of the Factor Xa inhibitors and the direct thrombin inhibitor, dabigatran.(26)(27)(28)

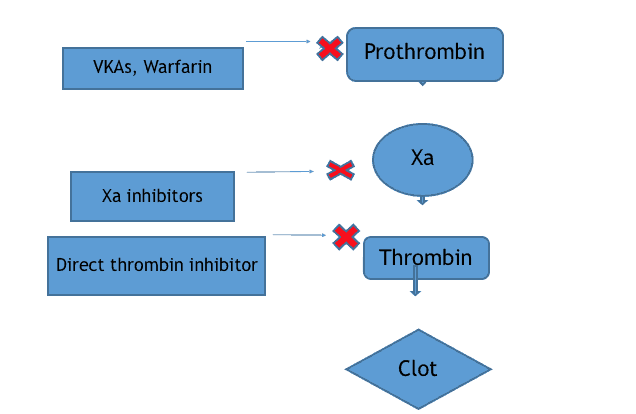

Here’s a visual for you, so you can see the order in which the various enzymes in the blood clotting cascade act to form a clot:

Coagulation factors II (prothrombin), VII, IX, X Factor Xa Thrombin Fibrinogen/Fibrin CLOT

And here’s a diagram showing at which point in the clotting cascade the various anti-coagulant drugs do their work:

Coagulation factors II (prothrombin), VII, IX, X Factor Xa Thrombin Fibrinogen/Fibrin CLOT

The Bottom Line

-

If you are taking warfarin, you cannot take supplemental K2.

-

If you are taking one of the newer anti-coagulants, you can take supplemental K2.

If you are taking warfarin, the rate at which your blood clots (your INR) must be checked by your physician to balance your intake of vitamin K, even the vitamin K1 in leafy green vegetables, with your required drug dose. You will not benefit from vitamin K2; even taken at a dose too low to benefit your bones, it will disrupt your INR causing you to need a higher dose of warfarin, which will then block vitamin K recycling, preventing vitamin K2 from activating the vitamin K-dependent proteins so important for healthy bones, osteocalcin and matrix Gla protein.

If you must take an anticoagulant medication and are currently taking warfarin, please discuss switching to one of the newer anticoagulants with your doctor. The warfarin drugs cause vitamin K insufficiency, calcification of soft tissues (blood vessels), osteoporosis, and cardiovascular and kidney disease. When taking the warfarin drugs, you must monitor your INR, avoid vitamin K2, and limit your intake of leafy greens, which are rich not only in vitamin K1 but also in calcium, magnesium and numerous trace minerals your bones must have for healthy new bone formation. The newer anticoagulant medications only need to be taken once daily, do not require INR monitoring, and most importantly do not restrict vitamin K1 or vitamin K2 intake from food or supplements.(29)

AlgaeCal has two bone-building formulations: AlgaeCal Basic, which does not contain vitamin K (for those who are on warfarin and are unable to switch to one of the newer anticoagulants and AlgaeCal Plus, which contains Vitamin K2 and has been clinically supported to increase bone density. Find out more here.

Sources:

- Cranenburg EC, Schurgers LJ, Vermeer C. Vitamin K: the coagulation vitamin that became omnipotent. PMID: 17598002Thromb Haemost. 2007 Jul;98(1):120-5.

- Theuwissen E, Smit E, Vermeer C. The role of vitamin K in soft-tissue calcification. Adv Nutr. 2012 Mar 1;3(2):166-73. doi: 10.3945/an.111.001628. PMID: 22516724

- McCann JC, Ames BN. Vitamin K, an example of triage theory: is micronutrient inadequacy linked to diseases of aging? Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 Oct;90(4):889-907. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27930. Epub 2009 Aug 19. PMID: 19692494

- Cranenburg EC, Koos R, Schurgers LJ, et al. Characterisation and potential diagnostic value of circulating matrix Gla protein (MGP) species. Thromb Haemost. 2010 Oct;104(4):811-22. Epub 2010 Aug 5. PMID: 20694284

- Poterucha TJ, Goldhaber SZ. Warfarin and Vascular Calcification. Am J Med. 2015 Dec 20. pii: S0002-9343(15)30031-0. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.11.032. [Epub ahead of print] PMID: 26714212

- Han KH, O’Neill WC. Increased Peripheral Arterial Calcification in Patients Receiving Warfarin. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016 Jan 25;5(1). pii: e002665. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002665. PMID: 26811161

- Tantisattamo E, Han KH, O’Neill WC. Increased vascular calcification in patients receiving warfarin. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015 Jan;35(1):237-42. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304392. Epub 2014 Oct 16. PMID: 25324574

- Danziger J. Vitamin K-dependent proteins, warfarin, and vascular calcification. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008 Sep;3(5):1504-10. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00770208. Epub 2008 May 21. PMID: 18495950

- Cozzolino M, Brandenburg V. Warfarin: to use or not to use in chronic kidney disease patients? J Nephrol. 2010 Nov-Dec;23(6):648-52. PMID: 20349408

- Namba S, Yamaoka-Tojo M, Hashikata T, et al. Long-term warfarin therapy and biomarkers for osteoporosis and atherosclerosis. BBA Clin. 2015 Aug 12;4:76-80. doi: 10.1016/j.bbacli.2015.08.002. eCollection 2015. PMID: 26674156

- Mazziotti G, Canalis E, Giustina A. Drug-induced osteoporosis: mechanisms and clinical implications. Am J Med. 2010 Oct;123(10):877-84. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.02.028. PMID: 20920685

- Pearson DA. Bone health and osteoporosis: the role of vitamin K and potential antagonism by anticoagulants. Nutr Clin Pract. 2007 Oct;22(5):517-44. PMID: 17906277

- Sugiyama T, Takaki T, Sakanaka K, et al. Warfarin-induced impairment of cortical bone material quality and compensatory adaptation of cortical bone structure to mechanical stimuli. J Endocrinol. 2007 Jul;194(1):213-22. PMID: 17592035

- Rejnmark L, Vestergaard P, Mosekilde L. Fracture risk in users of oral anticoagulants: a nationwide case-control study. Int J Cardiol. 2007 Jun 12;118(3):338-44. Epub 2006 Oct 18. PMID: 17055083

- Sugiyama T, Kugimiya F, Kono S, Kim YT, et al. Warfarin use and fracture risk: an evidence-based mechanistic insight. Osteoporos Int. 2015 Mar;26(3):1231-2. doi: 10.1007/s00198-014-2912-1. Epub 2014 Oct 10. PMID: 25300528

- Pearson DA. Bone health and osteoporosis: the role of vitamin K and potential antagonism by anticoagulants. Nutr Clin Pract. 2007 Oct;22(5):517-44. PMID: 17906277

- Tufano A, Coppola A, Contaldi P, et al. Oral anticoagulant drugs and the risk of osteoporosis: new anticoagulants better than old? Semin Thromb Hemost. 2015 Jun;41(4):382-8. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1543999. Epub 2015 Feb 19. PMID: 25703521

- Tantisattamo E, Han KH, O’Neill WC. Increased vascular calcification in patients receiving warfarin. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015 Jan;35(1):237-42. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304392. Epub 2014 Oct 16. PMID: 25324574

- .Poterucha TJ, Goldhaber SZ. Warfarin and Vascular Calcification. Am J Med. 2015 Dec 20. pii: S0002-9343(15)30031-0. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.11.032. [Epub ahead of print] PMID: 26714212

- Romley JA, Gong C, Jena AB, et al. Association between use of warfarin with common sulfonylureas and serious hypoglycemic events: retrospective cohort analysis. BMJ. 2015 Dec 7;351:h6223. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h6223. PMID: 26643108

- Dodson JA, Petrone A, Gagnon DR, Tinetti ME, et al. Incidence and Determinants of Traumatic Intracranial Bleeding Among Older Veterans Receiving Warfarin for Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA Cardiol. Published online March 09, 2016. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2015.0345. accessed 3-19-16 at http://cardiology.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=2499815

- Suárez-Pinilla M, Fernández-Rodríguez Á, Benavente-Fernández L, et al. Vitamin K antagonist-associated intracerebral hemorrhage: lessons from a devastating disease in the dawn of the new oral anticoagulants. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014 Apr;23(4):732-42. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2013.06.034. Epub 2013 Aug 15. PMID: 23954605

- Zapata-Wainberg G, Ximénez-Carrillo Rico Á, Benavente Fernández L, et al. Epidemiology of Intracranial Haemorrhages Associated with Vitamin K Antagonist Oral Anticoagulants in Spain: TAC Registry. Interv Neurol. 2015 Oct;4(1-2):52-8. doi: 10.1159/000437150. Epub 2015 Sep 18. PMID: 26600798

- Theuwissen E, Teunissen K, Spronk H, Hamulyák K, Cate HT, Shearer M, Vermeer C, Schurgers L. Effect of low-dose supplements of menaquinone-7 [vitamin K2(35)] on the stability of oral anticoagulant treatment: dose-response relationship in healthy volunteers. J Thromb Haemost. 2013 Mar 26. doi: 10.1111/jth.12203. [Epub ahead of print] PMID: 23530987

- McCann JC, Ames BN. Vitamin K, an example of triage theory: is micronutrient inadequacy linked to diseases of aging? Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 Oct;90(4):889-907. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27930. Epub 2009 Aug 19. PMID: 19692494

- Roca B, Roca M.The new oral anticoagulants: Reasonable alternatives to warfarin. Cleve Clin J Med. 2015 Dec;82(12):847-54. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.82a.14052. PMID: 26651894

- Siegal DM, Curnutte JT, Connolly SJ, et al. Andexanet Alfa for the Reversal of Factor Xa Inhibitor Activity. N Engl J Med. 2015 Dec 17;373(25):2413-24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510991. Epub 2015 Nov 11. PMID: 26559317

- O’Malley PA.The Antidote Is Finally Here! Idarucizumab, A Specific Reversal Agent for the Anticoagulant Effects of Dabigatran. Clin Nurse Spec. 2016 Mar-Apr;30(2):81-3. doi: 10.1097/NUR.0000000000000192. PMID: 26848896

- Wahlqvist ML, Tanaka K, Tzeng BH. Clinical decision-making for vitamin K-1 and K-2 deficiency and coronary artery calcification with warfarin therapy: are diet, factor Xa inhibitors or both the answer? Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2013;22(2):492-6. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.2013.22.3.21. PMID: 23945401

Sandra

April 2, 2016 , 8:51 amI previously read the Gouda cheese was the only cheese where you would get k2 from. In this article you did not mention Gouda. Have I been wasting my money buying Gouda or is it also a good source of k2?

Also for people with very infrequent afib , is aspirin still considered to be an adequate blood thinner? I read the link you provided but it mentioned aspirin could be used by people with regular heart rates. Thanks